Let’s start with a personal story.

Before my first son was born, I had a very specific idea of what made a mother good.

My whole life, I’d been good at things, competent and independent, able to muscle through with hard work and guidance from the right experts. So before my son was born, I studied up, reading baby sleep books and memorizing the five Ss and going to classes on breastfeeding and babywearing. I planned on nursing, and I imagined myself calmly rising in the night when the baby cried, feeding and soothing him, then going back to sleep. I had a husband, and he’d be an involved father, but also I assumed I’d be able to mostly do it on my own. I couldn’t imagine something as small as a baby would require me to ask for help. I’d earned an MFA and finished the coursework for a PhD before my baby was born, and I assumed I’d make good progress on my scholarship, continue publishing poems, attend conferences and readings, go out with friends, lose the baby weight without boring anyone by talking about it. I’d continue on with my life as I had before, accompanied by a baby.

You can see why this didn’t all go according to plan.

One day, when the baby was just three of four weeks old, I stood in the doorway of my husband’s home office, crying. “I’m sorry I’m not better at this,” I said. “I’m sorry I’m not good.”

“Are you kidding me?” he said. “Look at this baby. He’s beautiful.”

I don’t actually remember where the baby was as I sobbed about my shortcomings as a mother. He might have been asleep in the pack and play in our room, or wriggling in the rock and play beside my husband’s desk. I might have been holding him. And that uncertainty feels like part of the point: in the time I was certain I was a failure as a mother, I was looking everywhere but at my own child. I was looking out to the world–to the good moms at the new moms group I went to once before fleeing in shame, to the websites that promised to teach you how to make your baby sleep, to the books where mothers wrote about the sweetness of the newborn phase–and measuring myself against those external markers, and coming up short.

What I’d thought of as being a “good mom” was actually an impossible knot of conflicting standards and behaviors. Trying to be a good mom is a scam.

So why not aim for “good enough”?

There’s a watered-down version of the mid-century pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott in wide circulation. His theory of the “good-enough mother” has been translated into to a kind of “you got this, mama” Target-branded generic encouragement—the assurance that whatever you’re doing, you’re doing your best, and that’s fine.

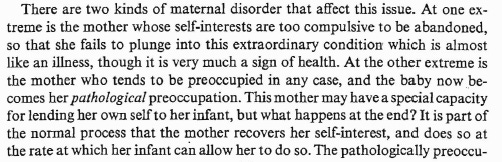

In the Winnicott I’ve read, there is a sliver-thin margin by which a woman (it’s always a woman) can be “good enough.” Writing about the first postpartum weeks, Winnicott described what he calls “primary maternal preoccupation,” a state of such complete devotion to the new baby that it would be an illness at any other time in a woman’s life. But there’s no guarantee that a mother will be able to achieve a correct degree of devotion, and Winnicott marks out the two ways a new mother can fail: by not being devoted enough, and by becoming too focused on the baby. In Winnicott’s words, “at one extreme is the mother whose self-interests are too compulsive to be abandoned,” meaning she cannot immerse herself fully in the baby. But the mother who becomes too focused on the baby is a danger, too, if the baby becomes her “pathological preoccupation.”

Got that? Immerse yourself in the baby, abandon your own self-interests, but not so much that you become overbearing.

More on Winnicott later. For now, this: even the idea of “good enough” introduces a rating system. If it’s possible to be good enough, it’s possible to be better, or to be bad.

“Good mother” or even the seemingly more chill “good-enough mother” is a set of impossible and ever-escalating standards. There’s no way any of us will ever measure up. And maybe that’s by design. When we start talking about “good moms” (or good wives or sisters or daughters or any of the rest of it), we should always be asking the question that’s buried underneath: good for whom?

Those ideals around what it means to be a “good mother” have never really been about what babies and families need. Instead, they’ve but shapeshifted in response to each era’s cultural and economic pressures. This was true for my mother, a divorced working mother in the era of Murphy Brown and debates about whether women really could “have it all,” and it was true for her mother, who, despite her degree in economics and career aspirations, became a small-town 50s housewife. And in our time the pandemic has cast a bright spotlight on the impossible standards and lack of structural support for American mothers: a “good mother” in the pandemic is still doing everything, but now she’s doing it all at once and without much help.

This newsletter is about giving up on being good and becoming something new.

I’m interested in the intersection of motherhood—the institution—and mothering, which is the act of care. Motherhood as a noun is an identity and a social performance; for me, mothering, as in the verb, is what really matters. I learned this distinction from Dani McClain, whose book We Live for the We: The Political Power of Black Motherhood, has shaped my thinking so profoundly. McClain explains, drawing on Revolutionary Mothering, a really remarkable book edited by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, China Martens, and Mai’a Williams, that “mothering is an action done by a range of people, including grandmothers, aunts, and queer and gender noncomforming people who don’t identify as women but who see themselves engaging in, as Gumbs puts it, ‘the practice of creating, nurturing, affirming, and supporting life.’”

In my own life, I became a mother through the support and caregiving of the community around me. I had two dear friends, Lauren and Ana, who met me and the baby for coffee and pastries most Tuesdays, and one day, I watched in amazement, as Lauren soothed the baby by draping the light swaddle blanket above his head to block some of the light and sound that had been bothering him. She’d been watching him and could see that he was overstimulated.

And what I love about mothering as a verb is that it isn’t just women’s work. One Saturday, we had friends over and everyone had gathered in the kitchen. I left the baby strapped inside his swing in the corner of the living room while I went to get something from upstairs. When I came back in, our friend Greg had moved a chair so he was sitting beside the baby, chatting with him about Penn State football while the baby watched the mobile above him spin. It hadn’t occurred to me that anyone else would keep the baby company in my absence, but I think Greg saw him as a tiny person who might not want to be alone. Mothering helps us move beyond the ideal of the omnipotent, self-sufficient good mother and think instead about a whole community of care.

If I could reach back in time to that woman standing in a doorway, sobbing, I would tell her this: stop trying to be good. (You do not have to be good.) That baby doesn’t need a good mom. He needs a good creature who will look down at his sweet particular face.